Students, this page has 8 sections to educate you about copyright in regards to your time in education. The first 7 can be navigated to by the different tabs. The last one is in it's own box below.

Copyright and Education

Copyright is determined by the country in which the product was made tangible. Since we are located with the United States information provided here reflects U.S. laws. The information presented here is intended for informational or educational purposes only and should not be construed as legal advice. If you have specific legal questions pertaining to copyright or intellectual property please contact your lawyer.

What is Copyright?

Copyright is a legal protection in the United States that allows authors and other creators to control their original, creative work. The work must be "fixed in a tangible medium of expression" - i.e. written on a piece of paper, saved on a computer hard drive, or recorded audio or video. In general, copyright holders have the exclusive right to do, and to authorize others to do, the following:

- Reproduce the work in whole or in part;

- Prepare derivative works, such as translations, dramatizations, and musical arrangements;

- Distribute copies of the work by sale, gift, rental, or loan;

- Publicly perform the work;

- Publicly display the work.

What is protected by copyright?

See What Does Copyright Protect? FAQ from the U.S. Copyright Office.

How do works acquire copyright?

Copyright occurs automatically at the creation of a new work. You are no longer required to provide a copyright notice within your work to receive copyright protection.

|

Copyright Notice

|

When do works copyright expire?

For works created since March 1, 1989, copyright lasts from the moment a work is created until 70 years after the death of the author, except for works produced by anonymous, pseudonyms, or for hire where copyright lasts 95 years from publication or 120 years from the date of creation. Works created before this date can have various copyright protection. The Digital Copyright Slider can be used to help define how long the protection of an item may last.

More information from the U.S. Copyright Office:

- § (Section) 102. Subject Matter of Copyright

- § 103. Compilations and derivative works

- § 104. National origin

- § 108 Limitations on exclusive rights: Reproduction by libraries and archives

- Circular 14: Copyright in Derivative Works and Compilations

- Circular 1: Copyright Basics

- Notices of Restored Copyrights

The creator usually is the initial copyright holder. If two or more people jointly create a work, they are joint holders of the copyright, with equal rights. Here are some examples of the exclusive rights of copyright holders that you now have the freedom to exercise:

- Create derivative works

- Reproduce the work in whole or in part

- Publicly perform or display the work

Create derivative works

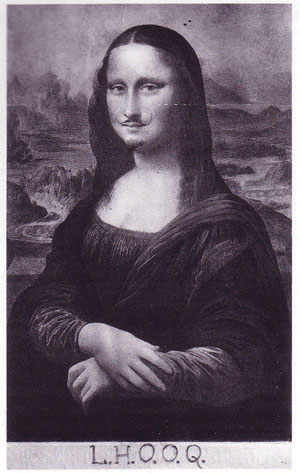

Derivative works are works that are based in whole or in part on the original work (e.g. a sequel or movie adaptation of a book), if you remix, rearrange, translate, adapt, and alter the original work to your preferences. Here is a great example of a derivative work based on a public domain work (the Mona Lisa):

|

|

|

Title: Mona Lisa |

Title: L.H.O.O.Q. |

In addition, Duchamp's derivative work is also in the public domain, so anyone could alter his derivative work, perhaps by lengthening the mustache or adding hair on the chest! (Note, however, that the work is still under copyright in its home country of France until 2039.)

Reproduce the work in whole or in part

For example, you could take the play Hamlet and make your own PDF copies of it, put annotations in it, make a cover for it, and distribute it or sell it online for others to read.

Is linking to content on the web considered copying or reproducing?

No. Linking to content online (i.e. web page, image or video) is just connecting the audience to the available resource. Citation and proper attribution to the owner of the work is expected. There is no legal requirement to request permission to link to a publicly available website.

Publicly perform or display the work

An example of publicly performing the work would be performing a play in front of an audience, and an example of displaying a work would be posting a photo on an online blog. Another example would be uploading a film online for others to view, such as on YouTube. Please note with films and other audiovisual works, you have to be careful, because there are layers of potentially copyrighted material in the film, such as the music/soundtrack, literature, characters, art, etc. An example of this complication involves the 1946 film It's a WonderfulLife, which entered the public domain in 1974 due to a clerical error in renewing its copyright. The film, which was not a box office hit when it was released, became suddenly popular after it entered the public domain due to the fact that broadcast television networks didn't have to pay royalties to air it. However, a few years later a lawsuit took place concerning the film's script and the soundtrack of the film; the plaintiff won, and although the film's images are technically in the public domain, the film is treated as if it is not in the public domain, because the music and the script are still protected by copyright. The film images, however, can be used freely, since they are still in the public domain.

Donna Reed and James Stewart, It's a Wonderful Life, 1946

Works Created Through Employment

If a work is created as a part of a person's employment, that work is a "work made for hire" and the copyright belongs to the employer, unless the employer explicitly grants rights to the employee in a signed agreement. Faculty writings (including "textbooks, scholarly monographs, trade publications, maps, charts, articles in popular magazines and newspapers, novels, nonfiction works, supporting materials, artistic works, syllabi, lecture notes, and like works") may or may not be treated as "work made for hire"; this is dependent on your local environment, therefore please see your local Intellectual Property Policy and any signed agreements (i.e. employment contract) for more information.

In the case of work by independent contractors or freelancers, the copyright belongs to the contractor or freelancer unless otherwise negotiated beforehand, and agreed to in writing. Please visit Circular 30: Works Made for Hire from the U.S. Copyright Office for more information on "work made for hire."

It is possible to transfer copyrights; this frequently happens as a part of publishing agreements. In many of these cases, the publisher then holds the copyright to a work, and not the author. A valid copyright transfer requires a written agreement. This includes "click through agreements" commonly found within submission and application forms.

If you are an employee at an institution in Florida, you may or may not hold the copyright to the content you create in the course of your employment. Generally, employees do not hold the copyright to the materials they create in the course of their work duties, especially if the content is specifically related to the institution. In this case, copyright is held by the institution and the work is considered a "work made for hire" under U.S. copyright law. You should consider the questions in the chart below to determine whether you or your institution holds the copyright to the work you create while working, teaching, writing, and/or creating content at your institution.

| Why/how did you create the work? | Who holds the copyright? | Exceptions |

|

As part of the normal course of your employment |

Institution |

The copyright may be held by you if:

|

|

As a employee using substantial institutional resources when creating the work |

Institution |

"Substantial use" is defined as receiving staff, salary, or material support beyond that normally provided to the creators. Institution owns the copyright to the specific materials but not to the intellectual content of the courseware. |

|

In the course of your employment for scholarly or artistic means |

Depends, see local agreements and Intellectual Property Policy |

The copyright may not be held by you if:

|

The United States Copyright Office is the number one authority on copyright in the US. Please refer to their documentation and instructions if you have additional questions about their website or information. Current copyright law can be found at http://copyright.gov/title17/.

§ 102 . Subject matter of copyright: In general

(a) Copyright protection subsists, in accordance with this title, in original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which they can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device. Works of authorship include the following categories:

(1) literary works;

(2) musical works, including any accompanying words;

(3) dramatic works, including any accompanying music;

(4) pantomimes and choreographic works;

(5) pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works;

(6) motion pictures and other audiovisual works;

(7) sound recordings; and

(8) architectural works.

(b) In no case does copyright protection for an original work of authorship extend to any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied in such work.

§ 106 . Exclusive rights in copyrighted works

Subject to sections 107 through 122, the owner of copyright under this title has the exclusive rights to do and to authorize any of the following:

(1) to reproduce the copyrighted work in copies or phonorecords;

(2) to prepare derivative works based upon the copyrighted work;

(3) to distribute copies or phonorecords of the copyrighted work to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership, or by rental, lease, or lending;

(4) in the case of literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic works, pantomimes, and motion pictures and other audiovisual works, to perform the copyrighted work publicly;

(5) in the case of literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic works, pantomimes, and pictorial, graphic, or sculptural works, including the individual images of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, to display the copyrighted work publicly; and

(6) in the case of sound recordings, to perform the copyrighted work publicly by means of a digital audio transmission.

§ 107 . Limitations on exclusive rights: Fair use

Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include—

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors.

§ 110 . Limitations on exclusive rights: Exemption of certain performances and displays

Notwithstanding the provisions of section 106, the following are not infringements of copyright:

(1) performance or display of a work by instructors or pupils in the course of face-to-face teaching activities of a nonprofit educational institution, in a classroom or similar place devoted to instruction, unless, in the case of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, the performance, or the display of individual images, is given by means of a copy that was not lawfully made under this title, and that the person responsible for the performance knew or had reason to believe was not lawfully made;

§ 110(2) . Technology, Education and Copyright Harmonization (TEACH) Act

(2) except with respect to a work produced or marketed primarily for performance or display as part of mediated instructional activities transmitted via digital networks, or a performance or display that is given by means of a copy or phonorecord that is not lawfully made and acquired under this title, and the transmitting government body or accredited nonprofit educational institution knew or had reason to believe was not lawfully made and acquired, the performance of a nondramatic literary or musical work or reasonable and limited portions of any other work, or display of a work in an amount comparable to that which is typically displayed in the course of a live classroom session, by or in the course of a transmission, if—

(A) the performance or display is made by, at the direction of, or under the actual supervision of an instructor as an integral part of a class session offered as a regular part of the systematic mediated instructional activities of a governmental body or an accredited nonprofit educational institution;

(B) the performance or display is directly related and of material assistance to the teaching content of the transmission;

(C) the transmission is made solely for, and, to the extent technologically feasible, the reception of such transmission is limited to—

(i) students officially enrolled in the course for which the transmission is made; or

(ii) officers or employees of governmental bodies as a part of their official duties or employment; and

(D) the transmitting body or institution—

(i) institutes policies regarding copyright, provides informational materials to faculty, students, and relevant staff members that accurately describe, and promote compliance with, the laws of the United States relating to copyright, and provides notice to students that materials used in connection with the course may be subject to copyright protection; and

(ii) in the case of digital transmissions—

(I) applies technological measures that reasonably prevent—

(aa) retention of the work in accessible form by recipients of the transmission from the transmitting body or institution for longer than the class session; and

(bb) unauthorized further dissemination of the work in accessible form by such recipients to others; and

(II) does not engage in conduct that could reasonably be expected to interfere with technological measures used by copyright owners to prevent such retention or unauthorized further dissemination;

Staying Legal: Four Steps for Reusing Materials in your Course

STEP ONE:

Find something without copyright protection. Check to see if what you need or something comparable is in the public domain. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary (2017) defines public domain as “the realm embracing property rights that belong to the community at large, are unprotected by copyright or patent, and are subject to appropriation by anyone.” Any content published in the United States (U.S.) before 1929, documents produced by the U.S. federal government, and publications from U.S. state governments are the most common materials in the public domain. Content in the public domain can also include some oddball or uncommon creations. These creations include objects created by nature, plants, animals, machines, random selection, or any objects not created by a human. For example, a flower pressed in a book might create a unique outline on the page, but that outline will not receive copyright; it was created by the flower and the book, and, by law, only human beings can own copyrights.

How can I determine what works are in the Public Domain?

Works created in the U.S. before 1930. Works that have a CC0 License or a Public Domain Mark (PDM) can be the easiest to determine whether they are in the public domain because they are clearly marked on the content.

|

CC0 (CC Zero) |

Public Domain Mark (PDM) |

| |

|

State and federal documents are sometimes produced by independent contractors; if this is the case then the work is only in the public domain if it was “work for hire.” If you are uncertain about the work’s copyright status, you may need to:

- Contact the contractor or related agency to determine if it is a “work for hire” and copyright protected or if the work is in the public domain. Works created by state and federal employees during their “official duty” will be in the public domain.

- Determine if works incorporated within state and federal documents are still protected which may prevent the work from entering the public domain. State and federal agencies should place a copyright notice with content that is still protected. Paper money, coins, and stamps have unique protections and should be further researched before being reused. You may find the Harvard website of assistance to help identify the relevant laws in each state, http://copyright.lib.harvard.edu/states/.

Determining if other types of works (e.g. works published between 1929-1989) are in the public domain may not be as simple. To aide in determining if a work is in public domain, find the answers to the following questions:

Is the work copyrightable? If no, then the work is in the public domain.

Has the work been published? If yes, also determine:

Was it published with a copyright notice?

Where and was it first published in the U.S.? When?

Is the work produced by a corporate author, work for hire, anonymous, or pseudonymous?

Is the work an original, derivative, or compilation of content?

STEP TWO:

Find something with an open or existing license. Check to see if what you need or something comparable has an existing license. Common instances in which materials have existing licenses include:

- Library-licensed content

If you are using library-licensed materials for an online course, such as on Canvas, you should consider providing perma-links, DOIs, or citations of the specific resource rather than including them in the learning management system (LMS) for students to download directly; this is beneficial for two to three reasons: Usage statistics for that resource will increase, which will let librarians in collection development know that the resource is being used. (When resources have low usage statistics, they have a greater chance of having their subscription canceled); Some of the licenses may not allow for electronic reuse in learning management systems, like the LMS; If you provide citations (with no links), students will better learn how to search and navigate the library databases for the specified resources. - Creative Commons Licensed content

CC Basics By Simonne and Stephen

If you find materials with CC licenses, you are free to use the content as long as you follow the license requirements. You can Search the Commons to find relevant content on a number of search engines and websites.

STEP THREE:

Determine if your use falls under an exemption

- Section 110(1): Exemption for face-to-face teaching, or; Section 110(2) (also known as the TEACH Act): exemption for online distance education. Beware that both Sections 110(1) and 110(2) are specifically for making copyrighted materials available to students enrolled in the course. Placing materials publicly online would not comply with these exemptions. Instructors often wish to use media, such as films and music, in the classroom. Section 110(1) and 110(2)/TEACH Act are specifically for displaying or performing copyrighted works during classroom sessions. This section allows instructors to use films, music, artwork, poetry, prose, and other copyrighted materials in part or in their entirety, if the amount used is necessary to meet the educational objectives of the course. The copies used must be lawfully made and obtained. While the law specifically refers to face-to-face classes, a secure online classroom that only officially enrolled students have access to, such as through Distance Learning, may be comparable to face-to-face teaching and use of copyrighted works in that active teaching format should be evaluated under similar standards. In online environments care should be used to limit the use of the clip to view-only and only for the duration necessary for education purposes.

- Please note that if you expect students to use the material outside the classroom (i.e. on their own time or as homework), or if you cannot rely on Sections 110(1) or 110(2), you should determine if you have a fair use (Section 107) instead. If you feel the documented evaluation of your use is fair then you are free to use the content, so long as it is a legal copy. If you decide to make copyrighted materials available publicly online rather than only available to students officially enrolled in the course (e.g. through Canvas), then you will need to evaluate if this use is a fair use. When the environment, such as where the materials will be made available, changes or the context of why you are sharing the materials changes (i.e. the first factor of fair use or the purpose of your use), your use must then be re-evaluated. Please note that exemptions in the law need to be determined each semester the content is used.

- Summaries of Fair Use Cases: Understanding previous fair use cases will help you in understanding this principle.

- The Four Factors of Fair Use: outlines the four factors and gives examples about what is and is not in favor of fair use.

-

Code of Best Practices in Fair Use from the Association of Research Libraries

-

Fair Use Evaluator This tool helps you make a fair use evaluation and provides a PDF document of your evaluation for your records.

STEP FOUR:

If necessary, request permission or purchase a license through a collective rights agency to use the item; it's not very common for an individual faculty member to purchase a license for use of a copyrighted work in the classroom. Faculty members in music, drama, and dance may be familiar with purchasing specific public performance licenses.

Model Permission Letters can be used to ask permission before posting content, from Dr. Kenneth D. Crews (formerly of Columbia University)

Please Note:

Even though created works may no longer be protected by copyright or patent law, these works may still have other types of protections. These protections can include trademark, publicity, privacy, HIPAA, and FERPA. If the work is still protected through one of these areas, then the content may technically be in the public domain but be afforded other protections that do not allow it to act as if it was in the public domain. For example, you want to publish some letters that were written many years ago, and you've determined that the letters are no longer protected by copyright; however, you discover that the letters reveal private information about individuals who are still alive today, and therefore, you may have to seek permission from those individuals before you decide to publish the letters.

While U.S. law does not require attribution to the creators of public domain works, it is considered ethical and moral to provide that information about creators/artists/authors.

As a copyright holder, you are encouraged to take an active role in managing your copyrights. As the original copyright holder you have the right to reproduce the work, prepare derivative works, distribute copies, and perform and display the work publicly. Many authors traditionally have transferred some or all of these rights to a commercial publisher in order to publish a journal article, proceeding, manuscript, textbook or book chapter. However, this is not your only option. The information below will help you to understand author rights and how to retain rights when publishing.

As a copyright holder and before working with a publisher or journal you should consider:

What author rights you would like to retain;

The Scholar's Copyright Addendum Engine will help you generate a PDF form that you can attach to a journal publisher's copyright agreement to ensure that you retain certain rights. You can further edit this PDF to specify even more rights. Specifying on the original contract that it is "subject to the attached addendum" is also a good idea. Be wary of click-through agreements. If in doubt, you can leave the webpage without clicking "accept" or "submit," and then you can contact the editor to negotiate your rights.The Addendum to Publication Agreement is a PDF addendum provided by SPARC (Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition) that allows you to retain all your rights under copyright. The Science Commons Publication Agreement allows you to specify what rights you are willing to grant to the publisher. You may also choose to simply Choose a Creative Commons License. If not, here are some basic rights you might want to retain include:

- Use for teaching purposes – in classroom, distance education, and lectures or seminars

- Posting to your personal website and/or to a subject or institutional repository

- Sharing with colleagues

- Making derivative works

What author rights the publisher or journal allows you to retain;

It’s important to research a publisher's copyright policies. You can search the SHERPA/RoMEO database to find information about specific journals and publishers; the database will let you know a publisher's policies on what version of an article you can archive and where you can archive the article (such as on an institutional repository, or on your personal website or academic social media profile).

And, whether the author rights the publisher grants you are sufficient for your needs.

Think about any rights you may want to secure now and in the future. It is highly recommended that you fully read and understand your contract before signing. Publisher copyright policies usually do not cover every aspect of a contract, and if you are publishing in a special issue of a journal, for example, there may be more specific stipulations in the contract that either restrict or expand your author rights. Know what rights it allows you to retain. There are 3 basic options when dealing with publishers: Transfer all copyrights to the publisher, transfer copyright but negotiate some or all of the rights with the publisher, or keep all copyrights.

Registering Your Copyright

Copyright protection is automatic and begins the moment the work is placed into a tangible form. A work does not need to be registered to be protected by copyright law. If copyright is automatic and processing can take over one year you may ask why one would want to register for copyright. Copyright registration can give you additional benefits like:

- Public record of work through a certificate of registration

- Only registered works may be eligible for statutory damages and attorney fees

- Works registered within five years become prima facie evidence in a court of law

Schedule of fees available at: http://copyright.gov/docs/fees.html.

You may register a work at any time while it is still in copyright. Registering is not difficult and can be done online. Visit the United States Copyright Office website for instructions and forms.

Licensing Your Works

The use of a Creative Commons license allows you to grant permission up front. This allows others to use your work in ways that you specify. This is also the only way for an author to require attribution in the U.S. Copyright holders can actually enter any license agreement under any terms they choose, however this needs to be in a written format.

You may also decide to submit your content directly into the public domain.

-

Catalog of Copyright EntriesThese PDF files can be used to find copyright renewal records for items that aren’t US Class A (books) renewals. Note: Copyright renewal had to occur sometime during the 28th year, however sometimes the Library of Congress could be slow in publishing said renewals. To maximize the search, look for the renewal records from the 27th to the 29th year.

-

Copyright.gov Copyright Records (pre-1978)This ongoing project presents records of copyright ownership from the United States Copyright Office for the period from July 1891 through December 1977.

-

Copyright.gov Public Catalog (1978-Present)This database shows records of all copyright registrations for all works dating from January 1, 1978, to the present, as well as renewals and recorded documents.

-

Copyright GenieThe Copyright Genie will walk you through the steps to determine if a work is in copyright and, if it is, when it will enter the public domain.

-

Copyright Renewals DatabaseThis is a database of copyright renewal records for US Class A (book) renewals received by the US Copyright Office between 1950 and 1992 for books published in the US between 1923 and 1963.

-

Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the U.S. - Reference TableThis table gives more context for determining the copyright status of an work, such as the length of the copyright term and the copyright status of works published or created outside the United States.

-

Copyright Term CalculatorUse information on hand to determine whether or not a specific work is in the public domain. This calculator takes into account the potential restoration of copyright for items published outside of the U.S. due to Uruguay Round Agreements Act.

-

Creative CommonsA non-profit organization that works to increase the amount of scholarly works (cultural, educational, and scientific content) in "the commons" — the body of work that is available to the public for free and legal sharing, use, re-purposing, and re-mixing.

-

Creative Commons License ToolFollow the steps to choose the appropriate Creative Commons license for your creative or scholarly work.

-

Digital Copyright SliderFrom the ALA Office for Information Technology Policy, a visual and interactive way to figure out if something is under copyright.

-

Exceptions for Instructors eTool GuideThis tool helps you determine if your intended use meets the requirements set out in the law and provides a PDF document for your records.

-

Fair Use EvaluatorThis tool helps you make a fair use evaluation and provides a PDF document of your evaluation for your records.

-

Internet ArchiveRenewal records for other media formats can be found in digital copies of the Catalog of Copyright Entries made available online through the Internet Archive and Online Books. When looking in these scanned copies, remember that copyright renewal had to take place in the 28th year, so look at records for 27 to 29 years after the copyright date.

-

List of Resources for Finding Works in the Public DomainThis source list is provided by the Public Domain Review, an online journal and not-for-profit project dedicated to the exploration of curious and compelling works from the history of art, literature, and ideas.

-

Online BooksRenewal records for other media formats can be found in digital copies of the Catalog of Copyright Entries made available online through the Internet Archive and Online Books. When looking in these scanned copies, remember that copyright renewal had to take place in the 28th year, so look at records for 27 to 29 years after the copyright date.

-

Public Domain SherpaThis site is an excellent resource and guide for understanding the public domain and copyright as it pertains to books, maps, photos, sheet music, and sound recordings. It is administered by an attorney and writer who is passionate about copyright and trademark issues, licensing, and contract negotiation.

-

Science CommonsA Creative Commons project "meant to lift legal and technical barriers to research and discovery".

-

Section 108 SpinnerUse this spinner/tool to find out if the reproduction of a work is permissible under Section 108: Limitations on exclusive rights: Reproduction by libraries and archives.

-

TEACH Act at the Copyright Crash CourseIntroduction to and explanation of the TEACH Act and how it may facilitate use of copyrighted works in the classroom. This site also includes a checklist to determine if a work qualifies.

-

Trademark and Public Domainan informative page on the Public Domain Sherpa website that offers insight into reusing works that are in the public domain (or whose copyrights have expired) yet include a trademark. Essentially, what it comes down to is how you use the trademark. To commit trademark infringement, you would have to use the trademark commercially and/or potentially confuse consumers regarding the identity of a product or service.

-

U.S. Copyright OfficeThe site where you can register your copyrights, renew copyrights, search copyright records, and learn more about copyright law.

Thesis and Dissertations

As a graduate or master student, you may be expected to write a thesis, dissertation, or honors report. While you may not hold copyright to all the images and figures you cite in your work, you hold the copyright to your thesis, dissertation, or honors report. Take a few moments to read "Copyright and Your Dissertation or Thesis: Ownership, Fair Use, and Your Rights and Responsibilities" from Columbia University, which will give you a better understanding of the common scenarios involving copyright encountered by graduate students when conducting research.

Copyright Page and Copyright Notice

Your thesis, dissertation, or honors report is an original work and is protected by copyright laws of the United States (title 17, U.S. Code). These laws give the copyright owner (in this case, you) exclusive rights to (or authorize others to) reproduce, distribute, produce derivative works, display, or perform the work. Copyright protection is automatic from the moment of creation, so copyright notice (e.g. © John Smith) is not legally required to receive protection. The copyright page is not required unless you plan to register for copyright, either through the U.S. Copyright Office or as part of the submission process to UMI/ProQuest (depending on your institution). However, it is highly recommended to include a copyright page within your work, because it communicates the copyright status of the work and gives others information about who to contact for permissions. You can include the copyright page even if you do not register for copyright. If you include a copyright page, the following information should appear on the page:

Copyright

© Firstname Lastname YYYY.

Reusing Content in your ETDR

When you reuse others' works, even if they are in the public domain (i.e. their copyright terms have expired or they never had copyright protection), you may not be infringing anyone's copyright, but you could be plagiarizing if you do not properly cite the work. Please see the Plagiarism and Infringement section of this guide for more information. While proper citation is important, you must also comply with U.S. Copyright Law when reusing content in your ETDR. Please refer to the Copyright Reuse in Education information within this guide, which breaks down how to legally use content in four sequential steps, before reading about the types of content (below) that are commonly used in ETDRs.

Here are the common types of content you might be using in your ETDR:

- Charts, tables, and graphs

Depending on the type of figure you are using, the chart, table, or graph may have little to no copyright protection. Creativity is a condition of copyright protection, and often, charts, tables, and graphs are merely representations of data that is generated by a software program, such as Microsoft Excel, and thus many of them do not have copyright protection. Take a few moments to read the "Copyrightability of Tables, Charts, and Graphs" from the University of Michigan in order to become more familiar with these distinctions. If a work (e.g. a graph) has no copyright protection, then you are free to use the work. If you feel that the work may have a minimal level of creativity, then you may need to rely on fair use. If you obtained the figure from an Open Access (OA) journal, such as the Public Library of Science, the paper and any of the figures likely have a Creative Commons License that allows for the reuse of the work.

- Quotations

Short quotations of copyrighted material are generally considered fair use. If you are quoting from a work that is either in the public domain or has an open license, such as a Creative Commons License, then you do not have to worry about relying on an exemption in the law such as fair use.

- Pictorial and graphic materials

If you are using pictorial and graphic materials in your ETDR, The Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts is recommended reading, especially if you plan to use these types of material later in your career. The first principle (pages 9-10) outlines analytic writing, which will be central to writing your ETDR. Also see fair use information within this guide for more key points.

- Survey instruments and standardized tests

If you plan to include published survey instruments or standardized tests in your ETDR, you should obtain permission. Keep in mind that standardized test publishers generally do not want their tests widely circulated and are unlikely to grant permission to reproduce them.